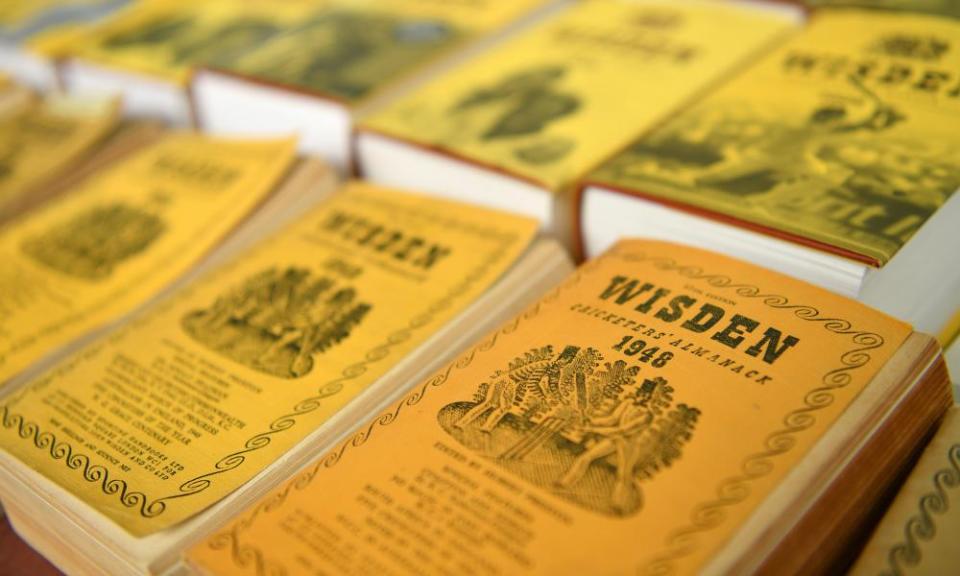

It arrives with a thunk through the door. It’s only little – 10.26 x 4.34 x 19.23cm – but possesses a heft that belies its corporeal state. That will be the molecularly thin pages, all 1,616 of them, crammed into an impossibly compact space, which chronicle the previous year’s runs and wickets and talking points.

But that only half explains the metaphysics at play. It’s too heavy to be a mere recounting of the observable world. Hold one up and raise it high. Feel the weight of it and notice how it seems to change size in your hand like Sauron’s ring. Something spiritual is at work here.

If you’re a cricket fan it’s difficult not to veer into hyperbole when writing on the significance of the Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack. The novelist Alec Waugh had it right when he first called it the game’s “bible”. It is a gateway to an ancient past, one that connects all readers of its gospels since it was first published in 1864, eight years before the inaugural international football match and more than a century before the launch of the Rugby World Cup.

Related: Jonny Bairstow is inaugural winner of new Wisden Trophy Test award

It evokes images of green pastures and teabreaks in the shires. And though it has moved with the times and now includes portions on the women’s game, Twenty20 franchises and something called the Hundred, its magic is found in the deep roots of its own heritage.

That is why one anonymous collector once parted with nearly £40,000 for a rare copy of the 1875 edition. Be honest. You’d have done the same if you had deep enough pockets.

Because a Wisden is not just for reading but for collecting and the more you have the greater the connection to cricket’s antiquity. Cast your mind back to the uncountable Zoom calls during lockdown. Did you notice the stacks of yellow proudly displayed like gold bars in the corner of your screens? I did. It seemed as if every other digital interaction was simply an opportunity for my friends and colleagues to show off their Wisden wealth. More seasoned journalists and punters needed multiple shelves to display their hoard.

In this latest iteration, No 160, Jon Hotten speaks to some of the most accomplished Wisden collectors and lifts the lid on their religious devotion. His research takes him to JW McKenzie, “a shop long beloved of cricket book collectors” where he is met by rows upon rows of relics with “pages as dry and fragile as autumn leaves”.

Hotten writes: “There is a sense of awe to them, and what they represent,” and as he holds a Wisden from 1879 he is ushered through a portal, “to another, lost time”.

I wasn’t aware of its transportive powers until starting my collection in 2017. Of course I had known about Wisden and all it represented, but coming from South Africa I was quick to dismiss what I considered to be another manifestation of English self-importance. Then I visited Lord’s and had the chance to feel the smooth dust jacket and experience for myself that logic-defying mass. Maybe I had been too hasty in my judgment. English cricket is dripping with pomposity but perhaps through the gaps between snobbery and disdain I may find something to love.

My opinion was fully altered in the summer of 2019 when I first bowled with a Dukes ball. Like reading a Wisden, bowling with that deep crimson orb that swings and seams as if under the spell of an invisible deity is an ethereal experience. After my first over the imprint of its pronounced seam lingered on my fingers like stigmata. I once was a trundler. Now, at least in the second division of the third tier of Middlesex league cricket, I was incarnated with the spirit of SF Barnes.

Recognising the sanctity of the 156g object, James Wallace made the pilgrimage to the holy sight of Shernhall Street in residential Walthamstow, east London. Here he encountered a nondescript grey-brick building that is the birthplace of every Dukes in the world and spoke with the man who oversees the operation, Dilip Jajodia. In an interview for the almanack the pair unravel a tale that includes Aberdeen Angus cows, the Crimean war, Stuart Broad and the Holocaust.

Elsewhere Gideon Haigh immortalises Shane Warne, a cricket demigod who was “always shrugging off the ordinary in quest of the extraordinary”. Patrick Kidd links the late Queen Elizabeth to the game while James Holland tells the story of famous players’ gravestones.

Life invariably brings the promise of death, and that is a theme that naturally dances its way throughout a book that continues to pay tribute to those no longer with us. But it is also brimming with life, best encapsulated by Tanya Aldred in her piece on cricket and autism.

There are warnings, too. Aldred, as she does better than any other writer, reminds us that the game’s future is at risk if we don’t adequately confront the climate crisisand, amid the rubble of the war in Ukraine, Alex Preston finds that cricket’s pulse continues to beat.

There is no single way to practise your faith and loving cricket is no different. Our strange sport is a broad church and this good book welcomes all. All it asks of you is to hold it in your hands and read it.

Article courtesy of

Source link